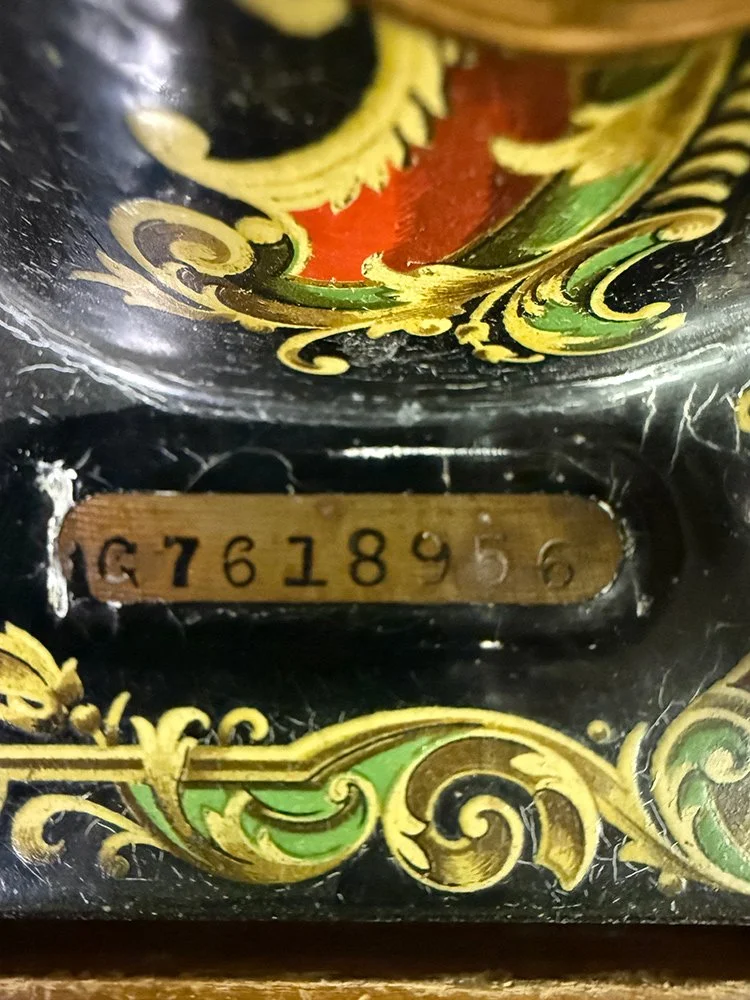

Singer Model 128 Sewing Machine

SHS1976.1.2 – Gift of George Johnstone

When we booked Discover Steampunk, we were delighted to see that the exhibition tied the art, literature, and fantastical inventions of the late 19th century to real inventions that came about as the result of the Industrial Revolution, as well as the impact they continue to have on society. We chose to highlight some of those inventions as Artifacts of the Month this summer, including this anything-but-humble portable Singer sewing machine dated by its serial number to a batch produced December 24, 1919.

Wait! What? Singer was Steampunk? Yes! Steampunk is nothing if not mechanical and industrial. Like many of the other inventors of his time, Isaac Singer was an actor, dreamer, and romantic. Singer and Edward C. Clark established I.M. Singer & Co. in 1851. They revolutionized mechanized sewing through simplicity, mass production, interchangeable parts, and payment plans, making his machine the first practical sewing machine for domestic use. It was the first complex standardized technology to be mass marketed.

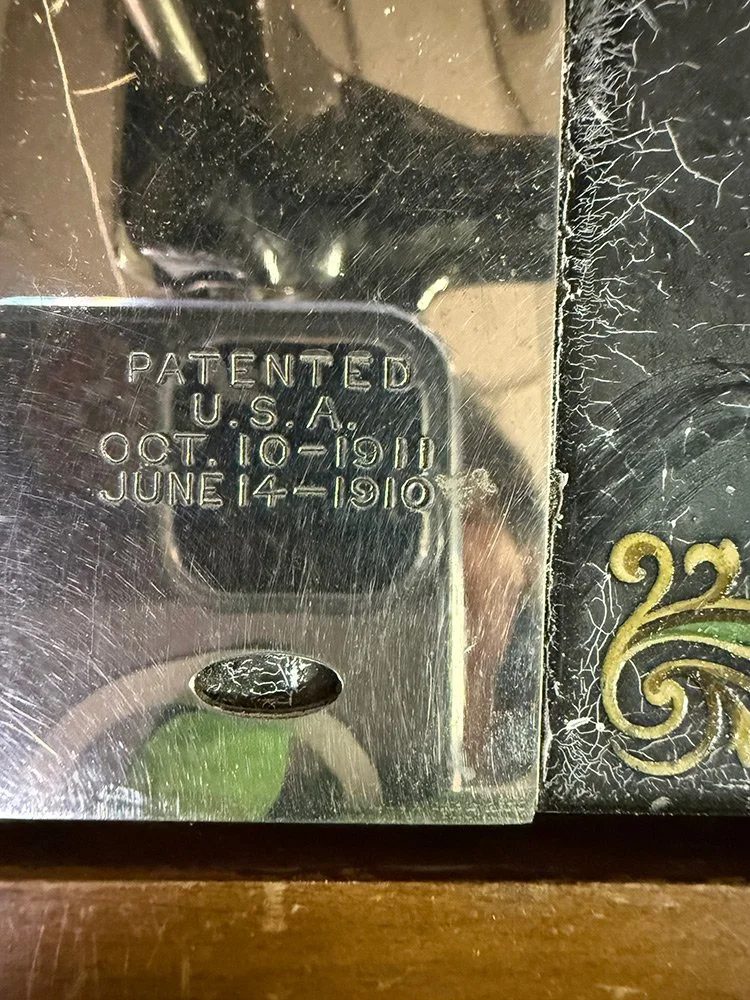

It was not without drama. In 1851, Singer patented an improved sewing machine that included a circular feed wheel, thread controller, and power transmission via gears and shafts. However, it was based on eye-pointed needle and lock stitch technology originally developed by Elias Howe. Howe won a patent infringement suit against Singer in 1854, but Singer consolidated enough patents to engage in mass production. By 1860, I.M. Singer & Co. was the largest manufacturer of sewing machines in the world. Production jumped from 810 units in 1853 to 262,316 units with cumulative sales of two million machines in 1876.

Nor were all the effects positive. These machines were easy to come by and easy to use, democratizing access to technology that freed people to sew and repair their own garments and household textiles quickly. Prices were so reasonable, and payment plans so generous, that most households could afford a sewing machine, even if that meant taking on paid sewing jobs to afford it. This ability to produce more created a demand for more woven cloth, which created a demand for more raw materials, which drove both technological ingenuities, such as the cotton gin, and the job market. This demand also drove the “sweat shops” of the industrial revolution and the exploitation of the workforce, including an increased need for slave labor before emancipation and for child labor. People moved from rural areas to cities looking for factory work. Those folks might have found themselves manufacturing a Singer sewing machine or using one professionally.

The featured machine is a Model 128. This portable machine powered by a hand crank was produced from the 1880s-1960s. The 128 was based on the earlier Model 28 with a major improvement developed in 1885. The “vibrating shuttle” bobbin driver replaced the older transverse shuttle design. The vibrating shuttle was a significant innovation towards the goal of a simple, fast, and reliable lockstitch sewing machine, and the design remained popular for decades.

In 1910, the company harnessed another Steampunk element, electricity, to create the first, workable electric sewing machine, which added speed to accuracy and reliability.

Singer did not just make sewing machines. During the World Wars the company switched their factories over to munitions production. Later, they diversified into office equipment, defense, and aerospace industries. In 1970, the introduced a small-business computer called the Singer System Ten, only to withdraw from the data processing market in 1976. Imagine what might have happened if they had remained in the industry. Your computer, or cellphone, might have the instantly recognizable “S” logo on it.